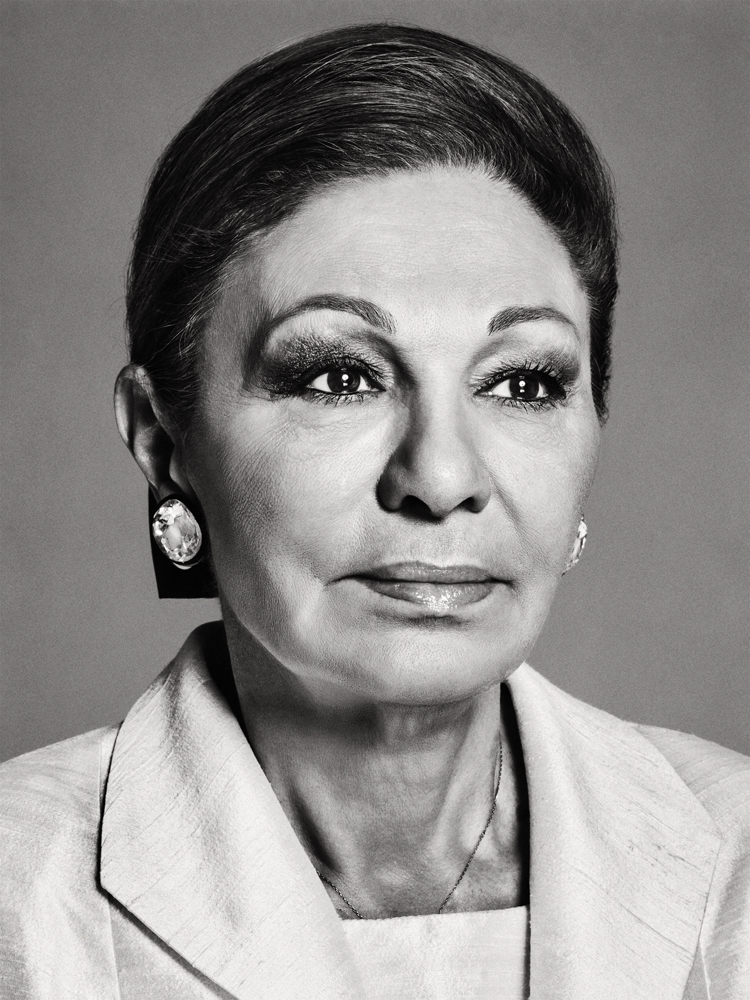

Stephie Pahlavi Zan sheds some light on the Distress and the Strength of His Beloved

"The last Empress of Persia" is My heart. There

is not a day that I do not have Her on My mind and in My soul. I adore

her. She is one of the best examples of strength, courage and grace that

I know.", says Stephie Pahlavi Zan. " Time passes so quickly and the

pain remains. We never imagined that We would ever go through the list

of tragedies and discover the false friends ( Countries ) that would

turn their backs on Us. HIH Empress Farah Diba Pahlavi was and remains

Our rock. She has gone through so much and remains strong, graceful and

continues to live Her life; despite the massive tragedies and

pitfalls.", states Stephie Pahlavi Zan. She is now 70 years old and has

spent the last 30 in exile. In this interview, by e-mail, she tells of

her anguish at Lajes Air Base one night in March 1980. Four months

later, Reza Pahlavi died in Cairo. Today she hopes that Tehran’s Islamic

regime has its days numbered.

Farah Diba Pahlavi has spent almost thirty years in exile but she

cannot forget the night of 23rd March 1980 when an Evergreen Airlines

DC9 in which she was travelling stopped over in the Azores. Officially

it was a refuelling stop but the aircraft was held up for several hours

on the tarmac without permission to take off. ‘It was an anxious

moment,’ the last Empress of Persia tells Pública during a rare

interview by

e-mail.

We have to go back in time to understand

what actually happened at Lajes Air Force Base, and which could have

changed the course of history. Farah Diba and her husband, Shah Mohammed

Reza Pahlavi, had been forced to leave Panama and they should have gone

on to Cairo where President Anwar Sadat had renewed his offer of

refuge. They had been fleeing for over a year. Several doors had been

closed to them after Ayatollah Khomeini had overthrown the monarchy.

Egypt had been the first stop in their exile on 16th January 1979 when

the imperial couple arrived in Aswan. But on the 22nd, Farah Diba and

the “king of kings”, who was suffering from terminal lymphoma, “a

well-guarded secret since 1974,” were already on their way to Morocco at

the invitation of King Hassan II. It was whilst they were staying at a

luxury villa in Marrakech that on 11th February Radio Tehran broadcast

the news most dreaded by the Shah: that “the Revolution had won and the

bastion of the dictatorship had capitulated.”

In her Memoirs the

Shahbanu (empress) confesses: “For a few moments I thought we had won.

In my view we were the good ones whilst they were the bastions of

horror. Unfortunately it was they who had won and who had overthrown the

last government (of Chapour Bakhtiar) nominated by my husband.” the

Shah, who had refused the requests of the officers of his personal staff

to shoot down the plane carrying Khomeini from Paris to the future

Islamic Republic, “remained silent for some time.” Their stay in

Morocco, where their children who had joined them from the United

States, became threatened when the Iranian masses began to demand the

return of the Emperor to be tried, and perhaps to be summarily executed.

This had already happened to hundreds of Army officers of the previous

regime. On 14th February, the U.S. Embassy in Tehran was temporarily

occupied by Revolutionary Guards. A French secret service emissary

arrived at King Hassan’s Palace in Rabat to warn that Khomeini had

ordered the kidnapping of members of the Moroccan royal family in

exchange for his guests.

Although King Hassan maintained his

solidarity, Farah Diba understood the seriousness of the situation. “It

was urgent to find another place of exile,” she states in her

autobiography, but “everybody turned their backs on us”. France had

refused, stating that it could not guarantee the safety of the emperors

who had fallen on hard times. The same happened with Switzerland and

Monaco. Mexico and Canada didn’t reply. The US said, “later, perhaps.”

Margaret Thatcher, who had promised support if she won the elections,

changed her mind when she became prime minister because, “it would be

bad for British interests.”

From Bahamas to Mexico

King

Hassan II put his private plane at the Pahlavi’s disposal. It was in

this aircraft that the Shah, the Shahbanu and the children (Reza,

Fahranaz, Ali-Reza and Leila) as well as a paediatrician, a governess,

several colonels and the Emperor’s “personal man-servant” left on 30th

March 1979 for Nassau, capital of the Bahamas. The archipelago did not

have diplomatic relations with Iran but the offer of asylum, obtained

thanks to Henry Kissinger, David Rockefeller and Jimmy Carter, had a

time limit: three months. Three weeks before the visas expired, the

Bahamian authorities said they would not renew the visas. But at the

request of Henry Kissinger, Mexico, under José Lopez Portillo, agreed to

accept the unwanted family. On 10th June 1979, Farah Diba, Mohammed

Reza and the accompanying party settled into Cuernavaca in the south, in

a house with a tropical garden and boasting scorpions on the walls.

This was the fourth site of exile in less than six months. The Emperor’s

health was worsening and since Mexico did not possess modern medical

facilities for cancer treatment and haematology, his doctors decided

that he should go into hospital in the United States. The Shahbanu was

saddened: “There was something rather vexing about being allowed into

the United States after it had refused us hospitality.” She also feared

hostile demonstrations but Mohammed Reza’s family and particularly his

twin sister, Ashraf, decided that he should be moved to New York where

she lived. They arrived there on 23rd October 1979 but before they

landed, President Carter called a meeting on the 19th of his inner

cabinet. Those present were: Walter Mondale, Cyrus Vance, Zbigniew

Brzezinski, Harold Brown and Hamilton Jordan. The unanimous opinion was

to allow H.M. the Shah to enter, as it was a case of “medical urgency.”

Carter was convinced but he did leave a question: “What will they advise

us to do when they (the Iranians) occupy our Embassy and turn our staff

into hostages?”

This fear, or presentiment, was justified. On

4th November 1979 Islamic students attacked and occupied what they

called the U.S. ”nest of spies” in Teheran and held 60 Embassy staff

hostage during 144 days. The Iranian Republic refused to believe that

the Shah was really ill. They suspected that Washington was preparing to

help him back into power as it had done in 1953 when the CIA overthrew

Mohammed Mossadegh’s government and put Mohammed Reza back on the

Peacock Throne.

Mossadegh’s fall was due to the fact that he had

dared to nationalise the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company and this action had

greatly annoyed Churchill. Today many political analysts, including the

CIA, agree that because British and Americans feared he might become an

ally of the U.S.S.R., this situation later opened the path for the rise

of Khomeini.

From New York to Panama

On the day following

his arrival in New York, on 24th October 1979, H.M. Mohammed Reza

Pahlavi underwent surgery that did not work out well. The news of his

internment spread quickly. He was able to hear through the window of the

hospital, where he was fighting for his life, the shouts of the

demonstrators crying, “Death to the Shah!” On 20th November, after some

of the hostages had been released, (only the Afro-Americans) from the US

Embassy in Tehran, Carter threatened to intervene militarily. On 28th

he stated he would not give in to blackmail to those who demanded the

extradition of the Emperor. He would only leave the U.S. when he had

recovered.

When the doctors decided the patient was ready to

leave hospital, the return trip to Cuernavaca was booked for 2nd

December. On the 30th November, however, President Portillo refused him

asylum. According to Farah Diba the price for this turnaround was Fidel

Castro’s promise that Cuba would vote in favour of Mexico’s entry onto

the UN Security Council if it did not allow the Shah to enter the

country.

The Carter Administration had no other solution than to

discreetly send the Persian Royal Family to Lackland Air Force Base in

Texas. It was a temporary stay that the State Department had no desire

in prolonging. Even South Africa, where apartheid still governed,

refused asylum. ‘We felt we were outcasts,’ complained Farah Diba.

On 12th December 1979, General Omar Torrijos, “Supreme Commander of the

Government” agreed to allow the Pahlevis into Panama. He installed them

in a four-room villa on the island of Contadora. Three months later,

Torrijos it appears, was persuaded by Sadegh Ghotbzadeh, “that he

conspired to be Iranian President” and that his house arrest would be

sufficient for the Iranian students to release the US hostages.

On being informed of the situation, the Empress gathered up courage and

phoned Jehane, Anwar Sadat’s wife to ask for help. “Come”, said her

friend, “We are waiting for you in Egypt.”

Carter became

concerned when he knew of this and tried to change Farah Diba’s mind:

“Your presence in Cairo threatens to undermine the already weak position

of President Sadat and threatens the peace efforts with Israel in the

Middle East.” On 22nd March, Carter phoned Sadat to try to persuade him

not to receive the Pahlavis. Sadat reacted angrily: “Jimmy, I want H.M.

the Shah here and alive!”

From the Azores to Cairo

H.M.

the Shah and H.M. the Shahbanu left for Cairo at 2 p.m. local time on

Sunday, 23rd March. That night the Evergreen Air Lines charter company

DC9 made a fuel stop at Lajes in the Azores. After waiting for one hour

Farah Diba began to fear the worst: “Was it an attempt to stop us

reaching Cairo? We were at an American airbase in an American plane,

therefore everything was possible.” On asking what the problem was, the

reply came back that the plane “required authorization to fly over

certain territories”. ‘

‘I asked the authorities to be allowed to

use a phone to contact a friend in Paris,’ recalls Farah Diba in the

interview to the Pública. ‘I informed this person of our situation: that

His Majesty was suffering from a very high fever, that it was very cold

inside the aircraft, of my concern over the uncertainty of the

situation and that everyone should be notified of the situation should

there be no further contact from us.

‘Many years later, sometime

in the 1990’s, I met the Portuguese Foreign Minister, Mr André Gonçalves

Pereira. He told me that the U.S. Embassy [in Lisbon] had been

questioned about our detention on the tarmac for over four hours and

that the reply had been that ‘we cannot give you any reason’ [later the

former minister would give his own version]. On the following day [24th

March 1980], the Portuguese Ambassador in Washington asked the State

Department the same question and, once again, the answer was “we cannot

give you any reason”,’ Later, Farah Diba found the reason for the

interminable delay. When one of the lawyers sent by Tehran to Panama was

preparing to deliver an extradition request he asked the U.S. to

intercept the Imperial couple’s aircraft as Saedegh Ghtbzadeh said he

was convinced he could manage to free the American hostages once the

announcement had been made of the detention of the royal couple.

The decision to hold the aircraft at Lajes was made by Hamilton Jordan,

chief of staff at the White House and a Carter confidant, although

Carter himself had not been advised of it. As no encouraging news had

arrived from Tehran, the aircraft was authorised to take off after a 4

hour holdup. On 24th March, when the extradition request was delivered,

the Pahlavis arrived in Cairo.

Farah Diba was convinced that

Torrijos “would not have hesitated to place the Shah under house

surveillance.” But would that have satisfied the Iranians? Whatever the

case, H.M. Mohammed Reza Pahlavi did not live for very much longer as he

died on 27th July. Sadat, who had installed him in the Kubbeh Palace,

gave him an imposing State funeral. The body lies in the El Rifai Mosque

where Farah Diba goes every year to pay tribute.

Meeting in the Algarve

‘Yes, it was me’ confirmed André Gonçalves Pereira to Pública. ‘I

became curious as to what had taken place in 1980 and, the following

year, as minister, I sought to find out what had happened at Lajes. The

aircraft had arrived at midnight and left at 8.00 a.m. [as stated by

Farah Diba]. This was strange. The stopover should have only taken half

an hour. The crew alleged a technical fault.’ On being asked officially,

the American officials merely replied, “they didn’t know.” They

couldn’t have replied to a sovereign state ‘we cannot give you any

justification’ added Gonçalves Pereira, as stated by the Empress in the

interview.

The former head of the Foreign Ministry checked his

diaries and found the moment when he had explained to the Shahbanu of

his interest in the Azores episode. ‘She came to dinner at my house in

the Algarve in July 1996 and it was then that we spoke about this

matter.’ The information that he had was that the Americans were

negotiating with the Iranians, through Algiers, the handover of the Shah

to the mullahs in exchange for the release of the hostages in Tehran.

Supposedly, the Islamic Republic’s demand was that the aircraft carrying

the Shah should deliver him to the Iranian capital. The U.S. only

agreed to leave him in Algiers. So the negotiations failed”.

Farah Diba’s version in her Memoirs states it was Panama and not

Algeria. The former minister states: ‘In matters of ultra-secret

diplomacy we can never be sure,’ except that ‘there weren’t any

technical reasons, rather political ones’ for the aircraft to be held

back and that Washington “really was negotiating the Shah’s

extradition.”

‘Farah Diba later wrote a letter to thank me. She

is a very intelligent woman and well informed. She has a regal bearing.

We still keep in touch occasionally. I remember a dinner in Paris when I

asked the Portuguese Ambassador to invite her.’ Over what had taken

place at Lajes, Gonçalves Pereira highlights “the contrast” in the

treatment given to the Shah by the U.S. and that by Egypt.

‘The

Carter Administration that was relatively straight forward and honest,

was ready to hand over the Shah, a fundamental ally of the U.S. in the

Middle East, whilst President Sadat, in an almost quixotic attitude,

agreed to receive him despite being threatened by Islamic

fundamentalism, that eventually assassinated him the following year. He

was a notable man.’

Revisiting Tehran

Today, almost 30

years after a trip that she had hoped would have been “a temporary

departure from the country,” Farah Diba is a harsh woman, in sharp

contrast with the meaning of her maiden name in Farsi that means “silk”.

She continues to defend the Shah’s actions and attributes his overthrow

to a conspiracy. She venerates him as a visionary leader, but many

however, including some of his staff, describe as being weak and

indecisive. One of them is the Iranian sociologist, Ehsan Naraghi who

was a critic (Savak, the secret police, forced him to leave the country

in 1969) and later a court adviser. In the book Des Palais du Chah aux

Prisons de la Révolution, Naraghi recalls one of the last audiences he

had with Mohammed Reza on 23rd September 1978 where the emperor who had

succeeded the Qajar Dynasty, asked him: “What is the source of this

rebellion? Who has instigated it? Who started this religious movement?”

The reply was: “But it was you, Your Majesty” The king of kings replied:

“Why me?”

“15 years ago in 1962”, explained Naraghi, “when you

visited the Qom Sanctuary [where Khomeini was a theologian], you openly

attacked the religious leaders and, in Parliament, you said that their

criticisms to land reform and to the emancipation of women were

reactionary. You were so violent, even insulting, that the person

responsible for the television broadcast had to censure your words. (…)

From then onwards, the religious leaders were forced, in order to reject

the accusation of being conservative, to take action and to prove that

they weren’t attached to an archaic social order. Supported by the vast

Shiite resources, they wished to show that they could be even more

revolutionary than Your Majesty with the White Revolution.”

Farah

Diba plays this down: ‘I can’t confirm if the conversation [with

Naraghi] and the Shah took place since I wasn’t present. In relation to

all the work he did, a French phrase comes to mind: ‘Il faut en prendre

et en laisser’. During the days of the Roman Empire it was said that if a

battle is won everyone participated but if a battle is lost, there is

only one to blame,’ she complains. ‘Iran occupies, in geo-strategic

terms, a very important position. It was becoming too powerful. Some

foreign interests began to feel threatened and they started a programme

of defamation against the monarchy in the media. They also courted and

encouraged the opposition within the country.’

‘I read an

interview by Ibrahim Yazdi [Opponent of the monarchy and minister in the

first year of the Islamic Revolution] where he speaks of his

relationship with the U.S. State Department and of how he passed on the

message that Ayatollah Khomeini valued human rights and the emancipation

of women. Lord Owen, who was Foreign Minister at the time [of the

Islamic Revolution] stated: “If we had known that the Shah was ill, this

would not have happened.” What does this mean? William H. Sullivan, who

was ambassador in Iran from 1977 to 1979, wrote about his meetings and

contacts with the Iranian opposition.’

“Let us not forget that it

was the Cold War era and that the Soviet Union who had a strong desire

to reach the warm waters of the Persian Gulf, was also a sponsor to and

played a role in the Iranian Communist Party, the Tudeh. There were

still other organised groups, such as the People’s Fedayeen (Maoists)

and the People’s Mujahedeen (Islamic Marxists), many of who were trained

in Cuban and Palestinian guerrilla camps. Members of these groups who

helped take Khomeini to power were later killed by the thousands.”

Does Farah Diba Pahlavi regret anything? She replies at length: ‘If we

had been better organised politically; if the political participation

had opened up before 1977; if the American Administration had been

different; if the British prime minister and French president had also

been different; if the Soviet Union had been Russia, if Khomeini had not

been allowed to come to Paris [from Iraq where the Shah had exiled

him]; if some Iranian intellectuals had not seen Khomeini’s face on the

moon; if people had listened to the Shah who said there we will remedy

the shortcomings and dissatisfactions; if the Western media had not

maliciously attacked the Shah and compared Khomeini to a spiritual

saviour, this tragedy would not have happened.’

Persopolis and Shiraz

Naraghi, the sociologist, said that he had tried, on several occasions,

to explain to the technocrats surrounding the Shah that “the great

civilization” desired by the Shah would lead to “a chaotic uprising”.

The emperor’s policy “divided a nation, a progressive minority on the

one hand and a traditionalist majority on the other – which undermined

the feelings of national solidarity and exposed [the Iranians] to a

completely new cultural conflict”.

Farah Diba acknowledges that

some of those responsible hid the people’s discontent from the Shah, but

she denies the existence of the division. This would mean, she

justifies, ‘that the majority of the Iranians is now happy which, as

everyone knows, is not true.’ She does not believe that lies, material

and moral corruption, flogging, stoning and dismemberment of people are

part of the valuable Iranian traditions. The majority of Iranians very

much wanted what ‘modern life’ offered such as schools, universities,

hospitals, stadiums, libraries, cultural centres, industries,

communications and their participation in the development of the

nation”.

The explanation found by the Shahbanu for the revolt of the Iranians against the Shah is different:

‘In Iran, after 1973, the increase in the price of oil did not please

foreign interests. There was a boom in development and the government

could not meet the people’s expectations. This created dissatisfaction

and fertile ground for the opposition, since it was well organised,

unlike us. Ayatollah Khomeini and his disciples promised paradise, free

vehicles, free transport, free utilities, free gasoline and other free

goods. Many believed in this but they opened the doors to hell. Today,

many regret having taken part in the street demonstrations. The younger

generation blame their parents for the current situation in Iran.’

The White Revolution’s land reform and emancipation of women were not,

in Mohammed Reza’s widow’s opinion, litigious: ‘The majority of the

population supported them,’ she states. ‘Obviously big landowners and

some religious fanatics didn’t agree with them. The good result out of

all this is that today’s Iran does not have a feudal system, despite the

pressures of the extremists, and the Islamic Republic did not manage to

change the rights of women to vote and to be elected.’ As for the

statement by some Iranians that the Shah “made a mistake in trying to

change from the bicycle stage to the jet plane without passing through

the stage of the motor car”, she is vehement:

‘I don’t believe

it. How can you tell people to wait 20 years [for progress]: when you

have all the natural resources and human wealth available? When I

travelled through the country people asked for more and better schools,

roads, clinics, water, electricity, etc.’

But this isn’t the

progress that many refer to, but rather the ostentation and the

provocation shown, for example, at the Shiraz Arts Festival, Farah

Diba’s personal project, inaugurated in 1967 and during the celebrations

of the 2,500 years of Persepolis in 1971. In Shiraz the biggest scandal

took place in 1978 when a Brazilian dance group performed explicit

sexual dances.

‘90 per cent of the Shiraz Festival programme

consisted of traditional music, dances and theatre and perhaps some 10

per cent of avant-garde, which doesn’t mean it was immoral,’ said the

Shahbanu to Pública. In Persepolis, the first royal city of the

Achaemenid Empire where vestiges of the palace of Darius I, successor of

Cyrus the Great, still survive, only the rich and powerful were

invited. The people were excluded. The costs were calculated at between

200 and 300 million dollars. Elizabeth Arden created a new line of

cosmetics and named it Farah. Lanvin designed the servant’s attire,

Maxim’s of Paris supplied the chefs and the catering. Except for the

Iranian caviar, all the food was supplied from France. The Empress

complained of “the exaggeration of the journalists”; she pointed out

that the infrastructures would last and justified the expense as “a

magnificent exercise in public relations” which helped many people to

“situate Iran on the map”.

Washington, New York and Paris

The only daughter of Colonel Sohrab Diba and Farideh Ghotbi, a plebeian

whom the Shah chose to guarantee his succession after two failed

marriages, she presently lives between Washington, New York and Paris.

Despite having opened a window of opportunity for Khomeini to launch his

revolution and closed the door to Mohammed Reza when he sought asylum,

France is still a country where Farah Diba Pahlavi feels comfortable.

‘I became familiar with European culture due to my studies

[architecture] in a French school,’ the Empress tells us. ‘My life story

has been followed by many in France and the French have been very kind

wherever I go,’

Paris was also the city where, in 1959, Farah

Diba personally met her future husband, twice divorced, in 1946 and in

1958. First from Fawsia bint Fuad, sister of King Farouk of Egypt whom

he married in 1939 when he was still heir to the throne and who bore him

a daughter, Shahnaz, and then from Soraya Esfandiari-Bakhtiari, “the

princess with the sad eyes”, whom he met in 1948 and married in 1951.

She suffered from infertility, but refused the Shah permission to have a

second wife as permitted by Islam so the union was annulled.

Mohammed Reza was 39 years old when he was introduced to Farah Diba, 20,

at a reception in the Iranian Embassy after a meeting with Charles de

Gaulle. She caused a good impression and this was enough for the

Emperor’s son-in-law, Ardehir Zahedi, Shahnaz’s husband to go ahead and

deal with the details for Farah Diba to become the fiancée the Shah was

seeking. An attempt to marry the king to the Catholic princess, Maria

Gabriela of Savoy, was found to be ill advised by the Vatican as “a

serious threat”.

Farah Diba accepted the Shah’s marriage proposal

on the day she celebrated her 21st birthday on 14th October. The

betrothal was officially announced on 21st November. The marriage that

included two ceremonies, took place on 21st December. Yves

Saint-Laurent, of the House of Dior designed the wedding dress,

embroidered with silver threads. The Carita sisters created a hairstyle

that featured a parting in the middle and with the temples covered. This

style became fashionable the world over. The diadem was a Crown jewel.

It was designed in the 50’s by the American, Harry Winston and weighed

two kilos.

Death in London

As Shahbanu, a title she

received on her wedding day and which the mullahs abolished, Farah Diba

Pahlavi led a dream life until the advent of Khomeini’s revolution. Not

that she faces financial problems (although she suffered a situation of

embezzlement of several million dollars). But following the death of her

husband she had to face the suicide of her daughter Leila who had

become a Valentino model. Suffering from a “chronic depression, low

self-esteem, nervous anorexia and bulimia”, she took a fatal dose of

“barbiturates and cocaine”, according to the autopsy. She was found dead

in her London apartment in June 2001. She was 31 years old.

‘The

loss of a child is always an open wound in the heart of a parent,’

Farah Diba laments. ‘Leila was a very intelligent girl, with good ideas,

but profoundly traumatised by the dramatic events in our lives. She was

very sociable and loved the company of those closest to her. When she

was depressed, she would open up: ‘I can help all my friends, but I’m

unable to help myself”.’

Deprived of Leila, the Shah’s widow

continued to dedicate herself to the rest of the family, particularly to

the oldest son, Reza, who proclaimed himself emperor after his father’s

death in Cairo. ‘Over the last 29 years the heir to the throne has been

very active in his contacts with many of his compatriots of different

ideologies both inside and outside Iran,’ says Farah Diba.

‘He

fights for a free, democratic and secular regime. And he believes that,

once free, the people will be able to choose the best form of

government. Traditionally, the king was always a factor for unification

amongst the different ethnic groups and religious minorities, because he

is above the political parties.’ She is also “blessed by the affection

of many Americans”, guarantees: ‘I have kept in touch with my people,

whether by correspondence, e-mail, telephone calls or interviews. I try

to help as much as I can.’

Somewhat bitterly she adds: ‘The

consequences [of the Shah’s fall from power] were dramatic for Iran and

for the region in general. Many should do some soul-searching about

their actions. Iran was setting up nuclear power stations, and nations

around the world were beating a path to its door to sell it equipment.

The world had confidence in the Shah’s wisdom so much so that Iran was a

10 per cent shareholder of Eurodif [company] in France.’

She

continues: ‘The regime survives by creating crises and seeking foreign

enemies, to revive sentiments of nationalism. This regime must not be

allowed to obtain nuclear weapons,’ She makes no appeal, however for

military intervention to stop the suspected Iranian uranium enrichment

programme.

‘The present regime is historically condemned to

disappear,’ she, who was once considered to be the most powerful woman

in the Middle East, concludes: ‘I hope that the world will help those

who value freedom. I’m confident that the light will overcome darkness

and that Iran, like the Phoenix, will soon rise from the ashes.’